The Plan is the Generator

The Plan is the Generator

Published in the Room One Thousand, Issue Five, April 2017.

The Plan is the Generator is a conceptual architectural design project that explores, in a very direct manner, the possibility of creating new architecture from old architecture—in particular, from the ground floor plans of canonical single-family homes.

The project begins with an analysis of the formal qualities exhibited in the plans of three projects: Robert Venturi’s Vanna Venturi House (My Mother’s House), 1964[1]; Louis Kahn’s Fisher House, 1967[2]; and Stanley Tigerman’s Daisy House, 1977[3]. Each plan’s compositional strategies, formal organization, embedded spatial relationships, inventory of elements, and variety of composite figures, among other characteristics, are carefully examined to not only understand the characteristics of these well-known built works, but to also speculate on the three-dimensional translation of their associated two-dimensional orthographic projections. This translation is the critical moment and the most pedagogically oriented aspect of The Plan is the Generator as a conceptual act that seeks to reimagine select artifacts of historical works as projective devices for the production of contemporary architecture.

House No. 64

Robert Venturi designed and constructed a house for his mother between 1962 and 1964. Venturi’s Vanna Venturi House, a physical manifesto, can be defined as a building that is asymmetrically symmetrical and concerns itself with an ironic double coding of architectural elements. This house has a front door that sits behind a centralized and sunken entry space beneath a broken pediment. On its front façade, it contains a strip window, a square window, and, rectangular window. At ground level, the house has a kitchen, two bedrooms, a bathroom, and a living room that are clustered together within a rectangle that provides a static boundary for an otherwise dynamic interplay of shapes nested within. A critical feature, the Vanna Venturi House has a central hearth from which the stair is carved. The space of the Vanna Venturi House can be read as both tectonically- and stereotomically-derived, further adding to the dualities and contradictions Venturi was writing into this early work.

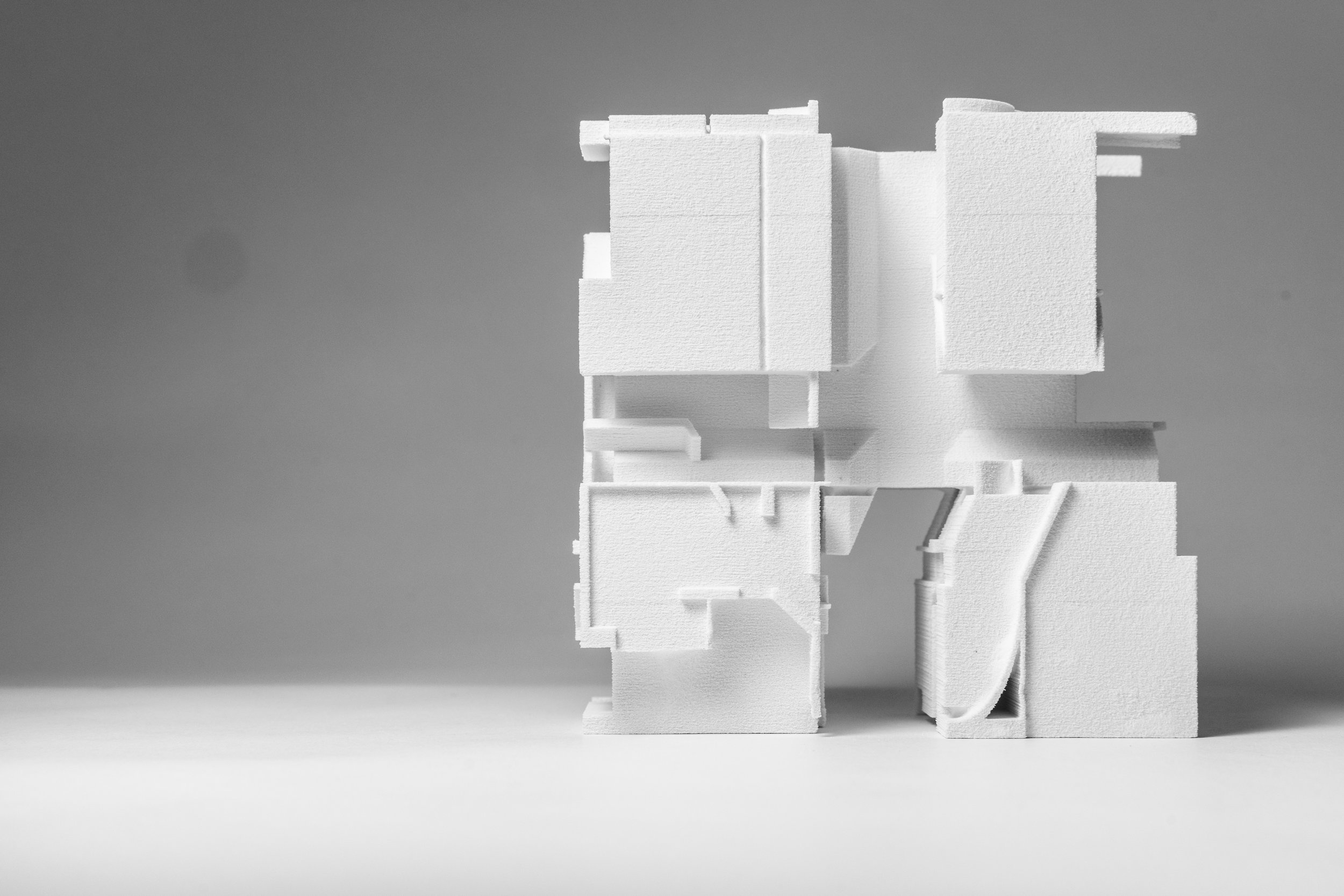

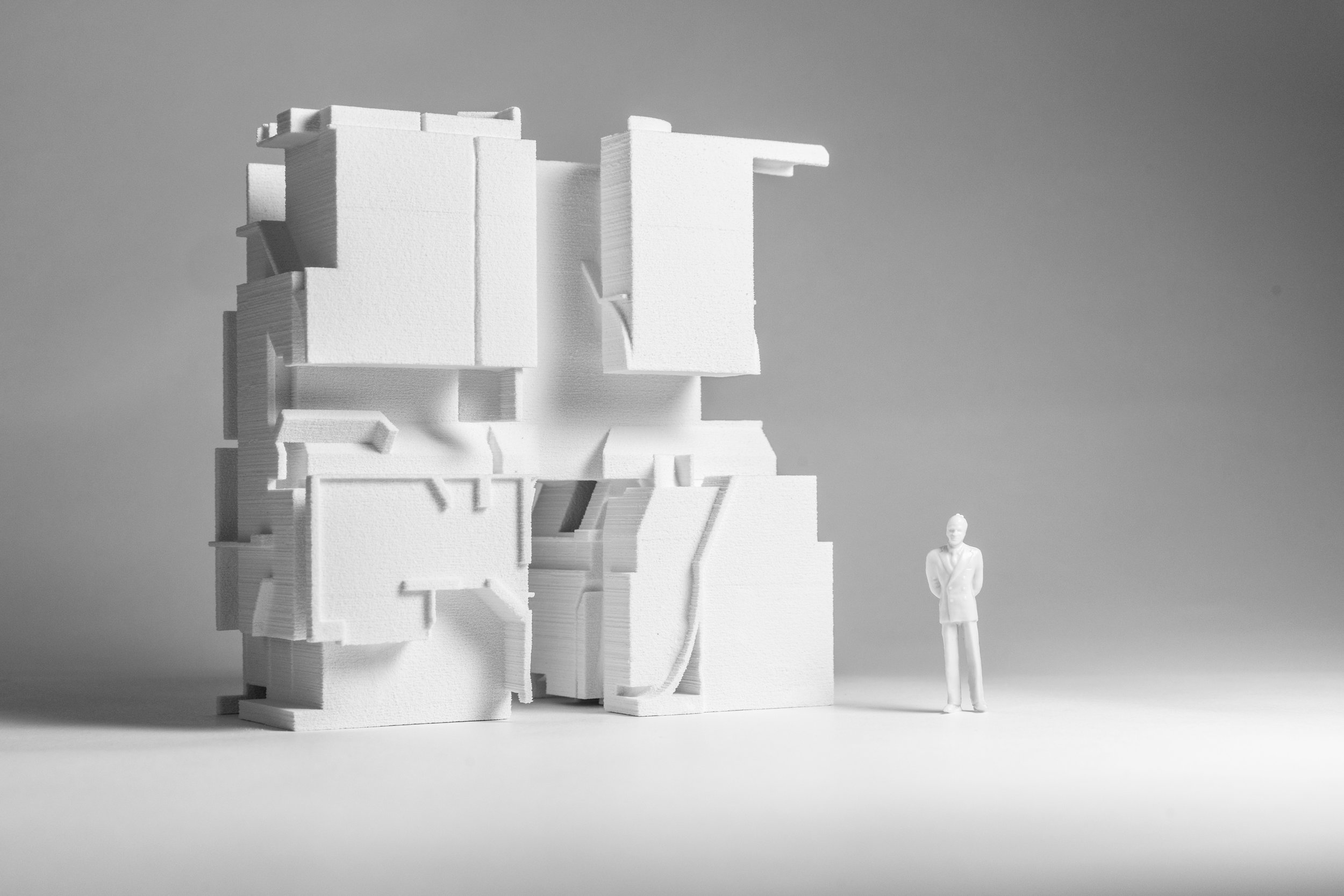

As a translation of the Vanna Venturi House, House No. 64 is characterized by a centralized void that constitutes its lower third and a cruciform recession that orients itself to the vertical axis. The front face of House No. 64 is articulated by physical features that both protrude from and carve away at the primary vertical surface. As is the case with the plan of the Vanna Venturi House, the elevation of House No. 64 exhibits a packing of irregular shapes within a regular rectangular boundary. The back face has less visual interest. House No. 64 is primarily concerned with the simultaneous tectonic and stereotomic production of mass and the interplay of line and surface.

House No. 67

An analysis of Louis Kahn’s Fisher House reveals a few key characteristics and defining features. In plan, one can observe a singular composite figure comprised of two dominant, yet incomplete shapes—two almost rectangles, one rotated 45-degrees about a point that sits outside of the first rectangle. This dislocated point of rotation causes the second rectangle to liberate itself from the first, creating a plan that is caught somewhere in between two intersecting, independent shapes and one articulated figure comprised of five complete lines and three trimmed, incomplete line segments. Experientially, the moment of intersection or interlocking provides for a lateral translation from one shape to the next. The programmatic imperatives of this break are clear—private activities such as sleeping and bathing are separated from activities that are often understood to be more public—living, cooking, and eating.

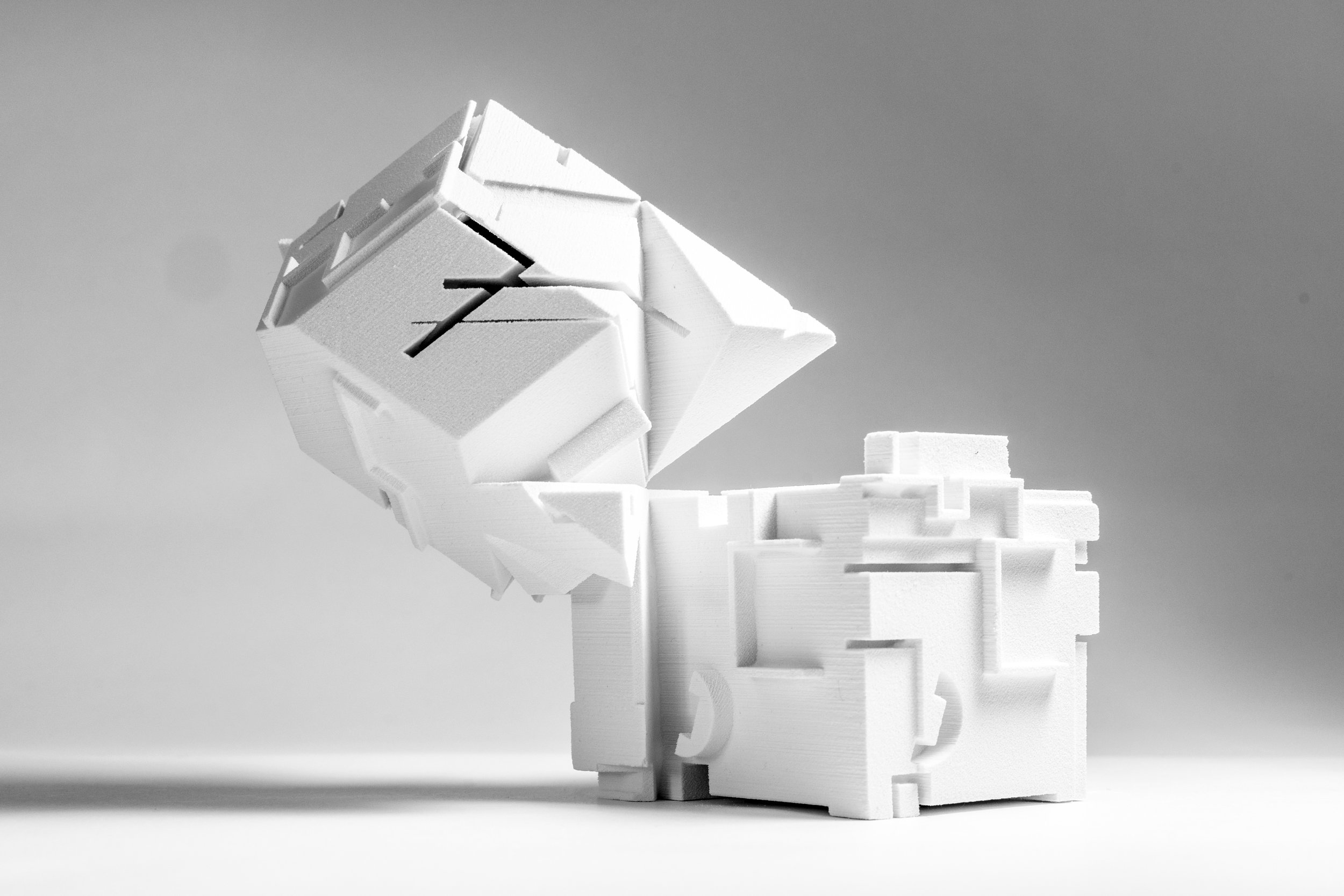

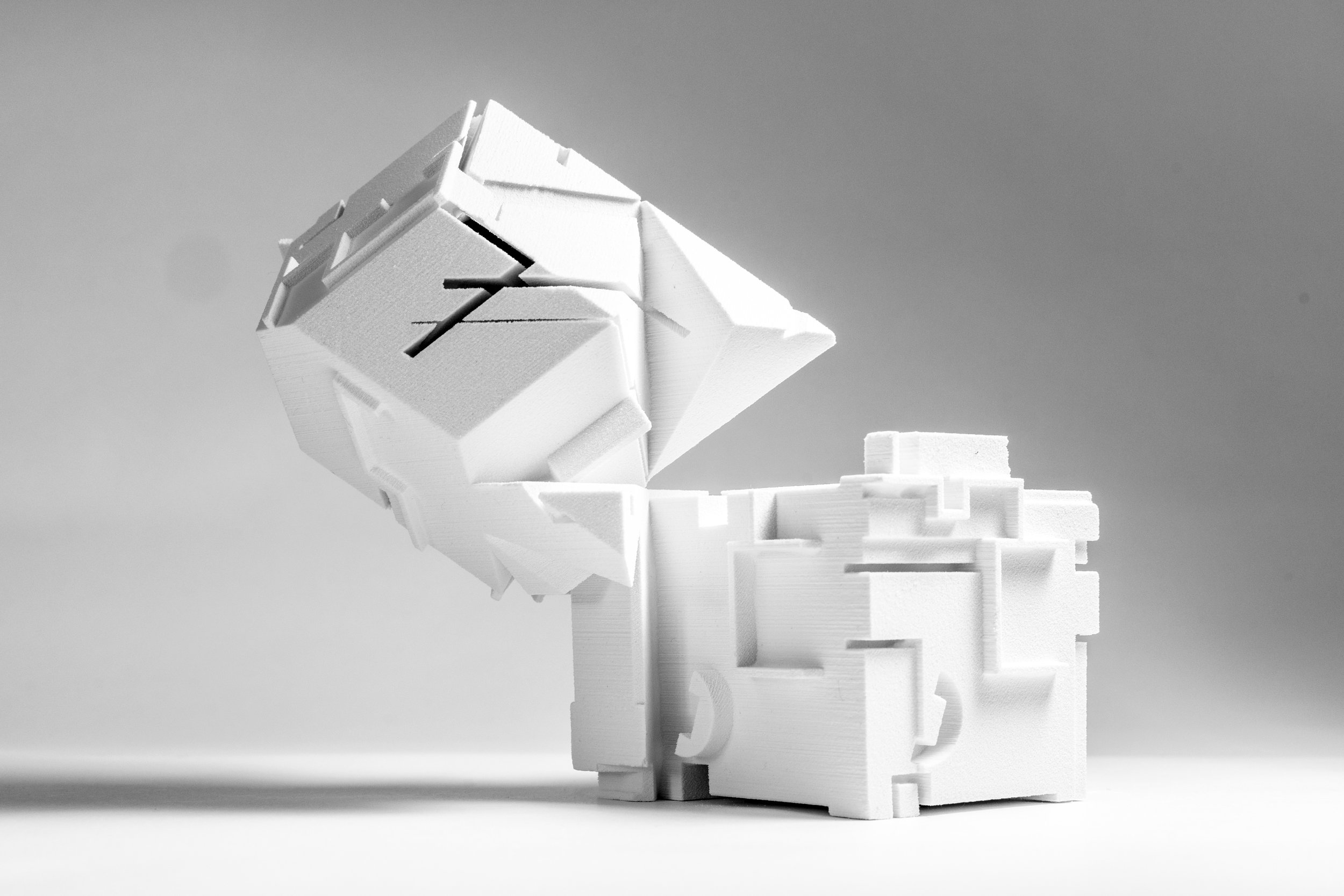

House No. 67 exhibits and exaggerates many of the formal features of the Kahn’s Fisher House and presents an aggressive formal revision of what was previously a clear and contained compositional move. The dislocation, once confined to plan, now operates in the x-, y-, and z-axes, resulting in a secondary volume teetering above the grounded volume in a somewhat precarious manner. The translation process, in part limited to two simple operations—extrude and trim—produces a distant cousin to the original, a body with the same DNA, but with a differentiated outward appearance. Where Kahn’s Fisher House is refined, simple, slow, and amiable; House No. 67 is coarse, complex, fast, and aggressive. House No. 67 is not the Fisher House, but remains indebted to it as an origin point.

House No. 77

Counter to the formal sensitivities exhibited in the plans of the Vanna Venturi House and the Fisher House, the plan of Stanley Tigerman’s Daisy House is concerned with figuration. The figure serves two functions—to provide comic relief to the client and to organize space within. As is the case in the Vanna Venturi House, the Daisy House exhibits a playful asymmetrical plan that masks itself as symmetrical. The main volume of the house contains the living spaces and is flanked by symmetrical protrusions that contain the bedrooms. The plan exhibits continuously controlled curvature—straight line segments alternating with partial circles from which the building mass is extruded. The plan geometry is considered at two scales, one at a much larger scale that enables the figural legibility and another that arranges itself to the scale of the body and to domestic activities.

House No. 77 doubles down on the legibility of the figure found in its precedent and presents the phallic figure not only in plan but also in elevation; a more appropriate picture plane for visually accessibility. On its vertical face, the translation borrows the alternating convex and concave curvatures to establish the presence of three seemingly separate building forms, whereas the front-side reveals an undulation that unites the disparate parts through protrusion and carving perpendicular to the viewing plan. House No. 77 uses the subdivision found in plan as a strategy applied to the surface of the mass to provide interest in the horizontal dimension and to balance the dominance of the vertical extrusion.

As a pedagogically motivated line of inquiry, The Plan is the Generator demonstrates how the discipline of architecture is constantly revitalized by the recurrent collusion between history and design, and between analysis and projection. The results provide a critical reflection on the timelessness of an architectural act and speculate on the nature of our discipline as being constructed from as a series of timely adventures that reveal architecture’s subservience to zeitgeist.